Preface

Tax revenue yield is influenced by both tax policy and tax administration. While tax policy design ensures responsiveness of potential revenue to overall economic growth, tax base and tax rates, tax administration seeks to secure potential tax revenues effectively and efficiently. It is because the two are inextricably linked that reform in tax administration is as important as that in tax policy.

In India, tax policy reforms have been accelerated since the economic liberalization unveiled in 1991. But no comprehensive reform in tax administration was undertaken in the same depth. Of course, changes in tax administration practices have occurred, albeit through a slow and incremental process reflecting the immediate requirements of the organization as opposed to much needed fundamental reform. The two administrative restructurings undertaken in 2001- 02 and 2013-14, of the two Boards, the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) and the Central Board of Excise and Customs (CBEC), were also aimed at expanding the tax administrations primarily by increasing tax assessment units, thereby giving more promotional avenues to officers and staff. But neither of the two restructurings was aimed at reorganizing the operations or their structures so as to make them oriented towards the needs of taxpayers.

Further, the restructurings have essentially stopped short of recognizing that direct and indirect tax services need to be delivered in a more synergistic manner so that there are gains for both taxpayers and the tax administration that should be buttressed by more rationalized enforcement activity, drawing upon information garnered from both direct and indirect taxes. Even within indirect taxes, service tax and excise duties are dealt with by separate commissionerates under the CBEC even though both are consumption taxes. The tax administration in the above regard did not, by and large, keep the prevalent global practices in view, i.e., it was not a benchmarked approach. Such a non-intersecting approach continues through the current restructuring process. The restructurings, therefore, have lacked a reform flavour. Since the focus is almost entirely on the extent of revenue collection irrespective of prevailing economic realities, any rise in collection could successfully mask the underlying need to fundamentally reform the tax administration. Indeed, the two tax administrations often attributed the gain in tax collection to the so-called restructuring.

What has been overlooked is that the impact of tax administration on revenue collection as opposed to the revenue gain due to economic growth needs to be separately recognized. The year-to-year high nominal growth in tax collection over and above the inflation rate may have generated a sense of complacency regarding administrative performance. One deleterious outcome has been the inexorable rise in disputes, reflecting rising pecuniary and non-pecuniary costs of compliance to the taxpayer. The tax administrations witnessed large tax revenues becoming uncollectible due to disputes emanating from tax demands that were of a protective nature, i.e., issued just to insure the tax officials against future liability. Such disputes were commonly viewed to have had adverse ramifications for the investment climate as business decisions became increasingly difficult in an environment of growing tax uncertainty.

The Commission (TARC), constituted to recommend reform exclusively in tax administration, was specifically mandated “to review the application of tax policies and tax laws in the context of global best practices and to recommend measures for reforms required in tax administration to enhance its effectiveness and efficiency.” The mandate reflected a deep concern of policymakers regarding the need for fundamental tax administration reform. Accordingly, the TARC tasked itself to address the thus-far missing elements of best practices in tax administration in a comprehensive manner. Such reform should aim at a vision that focuses on taxpayers and their relationship with the tax administration. This vision has to recognize the growing links between direct taxes and indirect taxes as occurring in most modernizing tax administrations in cross-country experience, and show the way to building an administrative structure that will bring accountability in the processes as well as greater outcome orientation. This would require the structure to be overhauled for purposive delivery and be so oriented that officers and staff are empowered while being given key performance indicators to reflect accountability and responsibility at both the individual and organizational levels. Only such a fundamental reform could ensure that the objective of bringing palpable benefits to taxpayers in terms of a transparent relationship and enhanced communication, ease of compliance, and quicker dispute resolution, is achieved.

In order to comply with the above mandate, the TARC identified four terms of reference, based on their relative importance, for immediate attention in its first report out. The selected terms of reference are:

- To review the existing organizational structure and recommend appropriate enhancements with special reference to deployment of workforce commensurate with functional requirements, capacity building, vigilance administration, responsibility and accountability of human resources, key performance indicators, staff assessment, grading and promotion systems, and structures to promote quality decision-making

at high policy levels.- To review the existing business processes of tax administration including the use of information and communication technology and recommend measures best suited to

the Indian context.- To review the existing mechanism of dispute resolution, time involved for resolution, and compliance cost and recommend measures for strengthening the process. This includes domestic and international taxation.

- To review existing mechanism and recommend measures for improved taxpayer services and taxpayers education programme. This includes mechanism for grievance redressal, simplified and timely disbursal of duty drawback, export incentives, rectification procedures and refunds etc.

While covering these terms of reference, the TARC decided to address the other segments of the terms of reference in its subsequent reports. Issues such as impact assessment analysis,

ii Executive Summary economic analytical models and strengthening database are examples of such aspects that are planned to be covered in future reports.

To achieve the desired goal, the TARC sought the views of its stakeholders, including the two Boards and its field offices, and the taxpayers. The TARC held meetings with the two Boards separately and of the officers, staff and their respective associations at the five metros of Bengaluru, Chennai, Delhi, Kolkata and Mumbai. Views from the directorates of the two Boards were separately ascertained keeping in view the policy dimension of their work. The TARC also met newly recruited officers at the National Academy of Direct Taxes and the National Academy of Customs, Excise and Narcotics to assess whether the training - in content as well as regularity, either at the induction stage or later - was sufficient to frame a structure that would be able to deliver in the manner outlined above. It was also imperative for the TARC to meet industry and professional associations at all five metros to ascertain their experience with the tax administrations, their expectations and suggestions for reform. One of the most important aspects of tax administration is the dispute resolution mechanism, since an inadequate or tardily functioning one could impede tax collection and create a climate of distrust. In view of this, the TARC had meetings with the President of CESTAT and Members of ITAT.

A list of such meetings is given at Annexure -I. The TARC is thankful to all the stakeholders for their suggestions and also for the free and frank discussions. These suggestions formed the basis of many of TARC’s recommendations. The TARC also acknowledges the co-operation and support of the CBDT and the CBEC in providing information and data that enabled TARC’s recommendations to be based on robust foundations.

Looking at the task at hand, which required in-depth analysis of various aspects relating to the four terms of reference, the TARC constituted six focus groups, comprising officers of the two tax administrations – former as well as current – and professionals from the private sector. The topics to be addressed by each focus group were framed after detailed deliberation within the TARC. The focus groups themselves met several times and came up with innovative suggestions by providing a forum for open and frank discussions with TARC Members. In the final analysis, the role of the focus groups in deliberating on various issues in depth and bringing in knowledge of calibrating them with global best practices was crucial in forming the TARC’s views. This helped the TARC to successfully thrash out many a new idea and emerge with a critical mass of recommendations. A list of participants in the focus groups is at Annexure -II.

The TARC’s recommendations were formulated at many meetings, formal and informal. A list of meetings in which TARC discussions were held is at Annexure – III. The TARC’s findings, conclusions and recommendations were unanimous, clearly pointing towards an overwhelming need for fundamental reform in tax administration that should successfully draw the attention of policymakers. Chapter I presents a comprehensive Executive Summary covering TARC’s coverage, main findings, conclusions and recommendations for the various aspects of the terms of reference covered in the report. The TARC believes this is the right moment in the light of a new reform environment that is expected to emerge precisely at this point of time.

iii The TARC places on record its appreciation of the Department of Revenue for providing support. It also thanks the Chief Commissioners of Income Tax and Central Excise and Customs of Bengaluru, Chennai, Delhi, Kolkata and Mumbai for organizing meetings with officers and staff and for providing support in organizing meetings with stakeholders.

The TARC also wishes to recognize the overarching support of the Secretary to the Commission in all aspects. The Director and Under Secretary as well as other support staff were also helpful. The work of three research consultants was important for the background studies that were carried out. The editor’s meticulous work at top speed was crucial. But for their intensive efforts, timely delivery of the report would not have been feasible.

New Delhi

30th May 2014

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

…to liberate the potential…you must first expand your imagination…things are always created twice: first in the workshop of the mind and only then, in reality. When you…take control…and imagine…in a state of total expectancy, dormant forces will awaken…to unlock the true potential…to create a kind of magic…forget about the past. Dare to dream that you are more than the sum of your current circumstances. Expect the best. You will be astonished at the results.

– Robin Sharma, in The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari

Public institutions, including government departments across the globe, need fundamental reform at least every decade, if not more frequently. This reflects the likely, and widely experienced, slide in the improvements made in the structure and practice that usually accompany fundamental reform. Tax administration is one such institution. To counter the anticipated slide, some reforming tax administrations have installed departments of change whose exclusive responsibility is to track the slack and sharpen, on a continuing basis, their productivity, accountability, cost effectiveness and, increasingly in a modernizing context, their service delivery. Some countries have developed the practice of subjecting their tax administration structure to occasional external examination to facilitate and introduce corrective measures.

India had not taken such measures in the past and the tax administration has experienced modest improvement that do not necessarily reflect global movement. Several committees suggested measures combining tax policy and tax administration, albeit selectively. Some committees took up overall public administration of which tax administration forms a component. Apparently for the first time, the Tax Administration Reform Commission (TARC) was set up by the government to examine and suggest reforms focused primarily on tax administration. This is a welcome first step.

Chapter I of the TARC’s report presents the Executive Summary. It is divided into four sections: first, the coverage of the report that presents the focus of each chapter, second, a detailed section on the TARC’s findings, third, a shorter section on the overall thrust of its conclusions and fourth, an elaborate section that lists its main recommendations.

1. Coverage

(1 Executive Summary is Chapter I of the TARC report. )

To achieve this, a framework has to be designed that should aim to reduce uncertainty in tax laws by providing clarity on tax obligations. Opening two-way communication channels between the tax departments and customers would be another aspect of the strategy.

Chapter II of the report covers these aspects. It also brings out practices in other advanced tax administrations. Some of the innovative approaches adopted by other countries have been highlighted, including recognising the ‘rights’ of the taxpayers.

No tax administration reform can be complete without looking deeply at the structure and management of the tax administration. While recognising that there is no unique model of the structure and management of a tax administration, there are some emerging cross-country patterns. The clear movement is towards a common organisation for direct taxes and indirect taxes. The TARC recognised that and decided to propose appropriate changes in the present structure in a calibrated manner where, to begin with, selected functions may be delivered through a common structure. One clear point to initiate this is the administration of large taxpayer units (LTUs). This would accommodate the prevailing LTUs, whose offices – currently in the five metros – perform both CBDT and CBEC functions, although in disjointed silos. Thus, the LTU experiment of structuring operations around a taxpayer segment has till now not gone far, the reasons being many. Another area of gaining such immediate synergy is in making tax laws. A further area of the TARC’s consideration was the need to reorganise the tax administration on a functional basis instead of its present organisation based primarily on territorial jurisdictions. The TARC has taken an approach to reform in a step-wise manner over time in recognition that the two tax administrations must be given time, albeit on a chalked out roadmap, to move to a fully integrated tax administration. But prior to full integration, a unified management structure through a common Board could be achieved in the next five years based on groundwork to be completed on data integration, common delivery structure for the benefit of taxpayers, and training of officers and staff based on comparable and benchmarked parameters.

Chapter III of the report deals with these aspects.

Tax administrations that do not allow specialisation among its officers and staff suffer in interfacing with high quality tax intermediaries and taxpayers. They also find it difficult to understand complex business transactions that require deep understanding and skill to decipher. These skills do not come with only theoretical exposure but while working on the subject for a minimum of 4-5 years, international experience revealing even periods as long as a decade during which an officer is encouraged to specialize. It is thus imperative to allow tax officers to develop specialisation in their work. Specialisation is not only required in audit functions, as is commonly held, but also in dispute resolution, taxpayer services, and in other functions of tax administrations such as HR, finance, tax analysis and ICT management.

Chapter IV of the report deals with the people function of the tax administrations, with training and specialisation forming important components. It also focuses on the wider HR needs of staff by identifying the need to introduce practices that have become common in modern tax administrations including mentoring, effective performance evaluation methods, for example, through assessment centres, and e-training.

Chapter V deals with dispute resolution and management. The TARC found in its analysis that the present dispute management structure should be converted into a separate vertical function so that the tax collection functions do not influence the resolution of disputes, which tends to occur at present. The current adversarial approach to disputes also needs to be transformed into one that is more collaborative and solution-oriented. Besides, the dispute structure needs to be modernised by bringing in alternative dispute resolution mechanisms through arbitration and conciliation. This may require legislative change. The role of regular interpretative statements has been emphasized to avoid disputes which otherwise arise due to ambiguity and imprecision in laws, rules and regulations. Equally important is taking due care for greater clarity at the law drafting stage itself.

Processes, by themselves, comprise an integral part of the reform along with structure, people and the use of technology in a tax administration.

Chapter VI deals with internal processes and the need to design their management structure to bring better delivery to taxpayers as well as to the tax departments. The TARC identified some key processes such as registration, return filing, and tax payment to be further expanded and sharpened. This would be in keeping with the recommendations made in Chapters II and III.

Both the CBDT and CBEC have been among the leading departments in the government in adopting ICT. Both have successfully implemented large projects that have made many processes convenient and transparent for the taxpayers and improved the efficiency of operations. However, there are still many gaps and a large room for improvement.

Chapter VII is on the need for a deeper penetration of information and communication technology (ICT) in the two tax departments. ICT has to form the backbone of improved service delivery and that could be better achieved through a special purpose vehicle (SPV) as expounded in that

chapter.

2. Critical Findings

At a macro level, the TARC found, first, that the Indian tax administration is in a vulnerable position due its static structure. For example, the recent “restructuring” of the two departments involved only an expansion in the number of posts without a corresponding reduction or re- allocation of resources away from less productive areas that is a quintessential element of modern restructuring and change. Second, the TARC found that the tax administration remains essentially unable to address rapidly emerging challenges on the domestic or international fronts, reflected in recent decisions that are far removed from international practice. Third, the TARC found that it should make recommendations that may appear to be far reaching and path breaking but are very much desirable and doable in the Indian context since they are benchmarked with prevailing global best practices.

Thus, it is fair to emphasize right at the beginning of this report that the TARC has not suggested any change that it believes cannot be carried out in the Indian context. Indeed, it is imperative that they be carried out given the prevailing tax administration characteristics in India. Some changes should be made with haste and others progressively so. The TARC has made specific suggestions of where the tax administration should make changes immediately, where it should position itself through continuing, self-generated reform in five years and, once appropriately empowered, where it should reach as a world class tax administration in ten years. In this perspective, a roadmap has been provided for complete and fundamental tax administration reform. Also, the recommendations made in different chapters of this report need to be viewed as a whole and not in isolated fragments, if the reform efforts are to bear the intended fruit. The TARC believes this is the right moment in the light of a new reform environment that is expected to emerge precisely at this point of time.

The major fault lines in the tax administration are listed as follows.

- Position of Revenue Secretary and autonomy of the two Boards: The TARC found that these matters are closely related and comprise the crucial shortcoming at the apex level. It also found that earlier taxation committees had addressed the issue time and again – as will be described below – though government action has not followed. The TARC found that its view closely parallels those of the earlier committees, modified however to reflect international experience that has since emerged.

There is a post of Revenue Secretary who occupies the apex position in the Revenue Department and is selected from the Indian Administration Service (IAS). He is likely to have little experience or background in tax administration at the national level and little familiarity with tax, including international tax, issues that are increasingly taking centre stage in emerging global challenges in taxation. yet he is the final signatory on decisions on tax policy and administration matters prior to their arrival for the Finance Minister’s consideration. The TARC found that this has translated to the Indian tax administration’s attention and concerns – in the form of the Revenue Secretary’s control over the CBDT and CBEC - to mainly represent the Revenue Secretary’s area of familiarity, i.e., general administration, in which he may be highly competent but which is likely to posses only thin links to the most challenging matters of tax policy making or modernizing tax administration in the light of current global practices. In a sense, this peculiar practice has assigned the ultimate responsibility for administration and financial control lying with the Revenue Secretary – Department of Revenue – rather than to the CBDT or CBEC.

This is not the first time that a government committee has found that this admixture is anomalous, and that the post of Revenue Secretary is superfluous. It was considered by the Tax Reforms Committee, 1992, chaired by Prof. Raja J. Chelliah. The Committee’s views were as follows:

“We recommend that (a) the two Boards should be given financial autonomy with separate financial advisers working under the supervision and control of the respective Chairman; (b) the Chairman of the two Boards should be given the status of Secretary to the government of India and the members of the rank of Special Secretary; and (c) the post of Revenue Secretary should be abolished.” (Para 9.27 of the Final Report Part – I)

The TARC’s finding regarding the role of the Revenue Secretary is congruent. It is surprising that government has so far not visited this matter and, as will be developed in

4 Executive Summary detail in this report, it is time to give renewed attention to it due to its adverse impact on the efficacy of the tax administration in India.

Interestingly, the Chelliah Committee not only recommended abolishing the post of Revenue Secretary, but also emphasized financial autonomy for the two Boards. To quote,

“…. the Boards should have financial autonomy and that the Chairmen should have a sufficiently high status. We recommend that the two Chairmen should be directly accountable to the Finance Minister insofar as matters relating to tax administration are concerned.” (Para 9.28 of the Final Report Part – I)

Selected matters relating to the administration/financing structure had been examined in the case of the CBDT by the even earlier Wanchoo Committee, 1971. It recommended making the Board an autonomous body, independent of the Ministry of Finance, with the Chairman enjoying a status equivalent to that of a Secretary to the Government of India as in the case of the Post & Telegraph Board. The subsequent Choksi Committee, 1978, reiterated that,

“… the Chairman of the Central Board of Direct Taxes should have the status of a Secretary to the Government of India and the Board should have adequate staff assistance and should be provided with personnel having necessary technical background and experience”. (II. 2.16 of Choksi Committee Report)

The issue of the administrative set up of direct taxes was also examined later by the Estimates Committee of Parliament. In its 10th report (1991-92), the Committee made the following recommendation in Para 3.77 of their report:

“The Committee note that the existence of Central Board of Direct Taxes as an independent statutory body dates back to 1964 when Central Board of Revenue Act, 1963 was enacted. The Board is responsible for administration of various direct tax laws and rules framed thereunder, and for assisting Government in formulation of fiscal policies and legislative proposals relating to Direct Taxes. They further find that apart from the field offices of the Income Tax Department, a number of attached offices also function directly under the Board and assist it in discharging its responsibilities. At present the Board comprises of (sic) 7 members one of whom is nominated as its Chairman. However, the Committee are surprised to note that the Government have not yet accorded appropriate rank and status to the Chairman and members of the Board….

The Committee wonder why the Chairman of the Board cannot be given the rank and status of Secretary of Government of India. The contention of the Ministry that there ought to be a Secretary, Department of Revenue, to coordinate the affairs of the two Boards, viz., CBDT and CBEC, isunacceptable to the Committee as in their opinion the two areas of Central revenues dealt with by the two Boards are fairly distinct from each other and do not require more coordination than that is necessary between the Ministries of Commerce and Finance, which are headed by independent Secretaries reporting to different Ministers. The Committee feel that at the Secretariat level whatever coordination is necessary can best be achieved through inter- ministerial or inter-departmental Committees and consultations. The Committee are amused at the contradictory stand taken by the Ministry in deeming the two departments viz. Income Tax and Customs and Central Excise to be more important than the Railway Board and simultaneously expressing themselves against conferring upon the head of these organizations the rank and status of a Secretary to Government of India particularly when the Chairman, Railway Board holds the rank of a Principal Secretary to Government of India. The Committee find no reason why similar status cannot as well be given to the Chairman of the Central Board of Direct Taxes and the Central Board of Excise and Customs.”

With regard to the Committee’s observation that the two Boards are “fairly distinct from each other and do not require more coordination than that is necessary”, the TARC notes that since 1991-92 international experience has clearly moved counter to the Committee’s observations and as noted in Chapter III, the dominant global trend is in the direction of unification of direct and indirect tax administrations and treating corporate tax and VAT/GST together as business taxes.

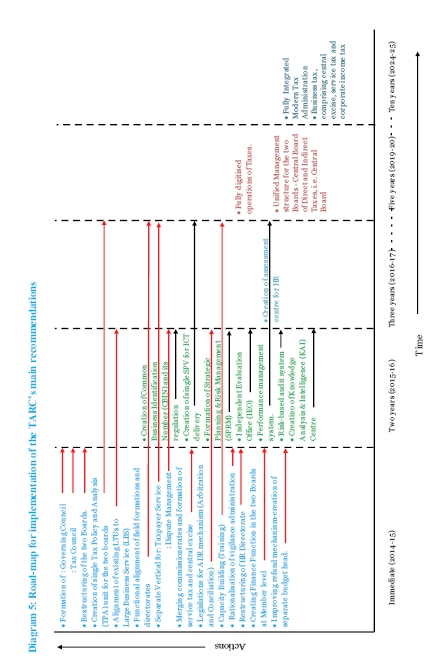

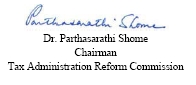

The TARC has worked along similar lines. First, it agrees that the post of Revenue Secretary does not merit presence in a modern tax administration. Instead, a Governing Council should be introduced with the chairs of the Boards alternating as its chairperson. In this manner, the TARC adds to the tenor of the Chelliah Committee in that India should benchmark itself with modernizing tax administrations by not only removing the position of Revenue Secretary but by replacing it with a Governing Council that should include members from the non-government sector as well. The Governing Council will oversee the functioning of the two Boards and approve broad strategies to be adopted by the tax administration to fulfil the objective of a more co-ordinated approach to the administration of the two taxes – direct and indirect – and create a structure which is independent. Such a co-ordinated approach also improves the focus of the tax administration towards its customers, or taxpayers. A depiction of the desired governance structure for large business service is given in Diagram 1. This has been discussed in detail in Chapter III of the report.

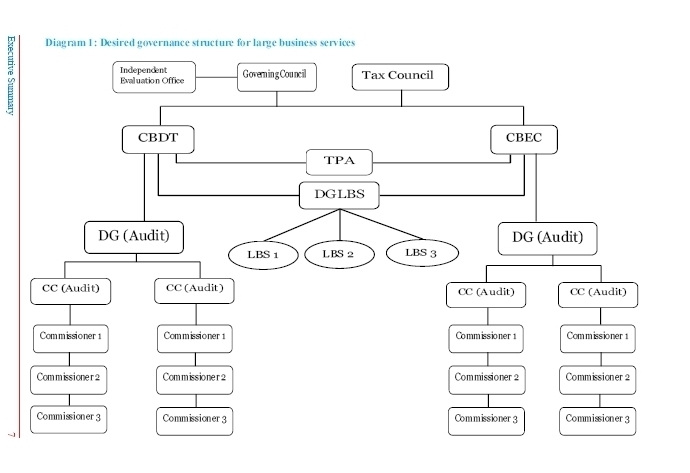

Second, synergy in tax policies and legislation between the two tax areas is to be achieved through a Tax Council, headed by the Chief Economic Adviser (CEA) at the Ministry of Finance. The Tax Council will bring the rigour of economic analysis and high precision in legislative drafting to tax laws so that tax laws are not only of assured quality, but are also coherent across tax types. Structure of the Tax Council and the Tax Policy and Analysis (TPA) unit, described in greater detail in Chapter III, is given in Diagram 2 below.

Diagram 2: Structure of Tax Council and Tax Policy and Analysis Unit

The TARC found that the CEA is more equipped to deal with the links between tax and economic policies than the Finance Secretary (who was given a role by the Chelliah Committee). This new pattern reflects prevalent global practice in which tax and the economy are recognized to be intrinsically linked. That link needs to be established in India rather than linking it with external administrative control, apparently to accommodate an administration oriented service.

The proposed structure would result in more autonomy in the functioning of the tax administration, which is unlikely to be achieved in the present structural framework as it fails to empower tax departments to carry out their assigned responsibilities efficiently. The Kelkar Committee, 2003 also recommended that both the CBDT and CBEC should be given requisite autonomy. The present functions of the DoR could easily be handled by the two Boards. The TARC could not identify the rationale for entrusting such functions to a separate body. Functions such as prevention and combating abuse of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances and illicit traffic therein, Smugglers and Foreign Exchange Manipulators (Forfeiture of Property) Act, 1976, and the administration of central sales tax can be looked after by the CBEC while the enforcement of the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999, and Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, can be looked

after by the CBDT. The administrative functions relating to the Authority for Advance Ruling, Settlement Commission and Ombudsman can be delivered through the respective

Boards.

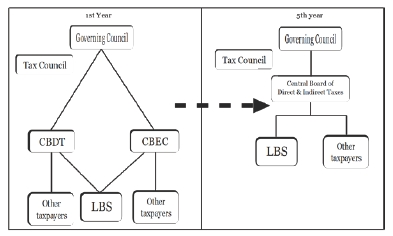

The Governing Council and Tax Council will operate as single entities over both Boards to achieve better tax governance. The Councils anticipate the eventual convergence of the two Boards. Over the next five years, the two tax departments would move to a unified management structure, i.e. a common Board and operate the services for both taxes, as shown in Diagram 3 below. This would pave the way over another five years to a fully integrated tax administration with corporate tax, excise duty and service tax, together comprising taxes on business. When major functions of the tax administration are organized along functional lines, and not on merely tax lines, it will enhance taxpayer as well as staff convenience. This reflects current global practice. This would, of course, not be at the cost of specialisation in different tax types. The description above is a snap-shot of the structure described in greater detail in Chapter III and the same is depicted below.

Diagram 3: Towards a unified structure of the two Boards in 5 years

Artificial separation of two tax Boards: The tax administration is divided into two Boards – CBEC and CBDT – whose Chairs and Members are selected from career tax officials, and who report to the Revenue Secretary. There are several crucial difficulties with the nature and practice of the two Boards. First, there is no rationale for a functional separation that fails to reflect the common global practice of the day. This is because many of the Members’ functions on the two sides repeat the same function that could be carried out ideally and optimally by the same official. This separation appears to accommodate the comfortable existence of Board Members rather than serve the interests of government in a sharp tax administration. Combining at least certain functions immediately would yield more Member positions in currently neglected areas. The Chelliah Committee had also recommended that the two Boards should operate in close co-ordination with each other. To quote:

“With the abolition of the post of Revenue Secretary some arrangement would have to be made to ensure supervision and coordination of the activities of the two Boards. While alternative institutional arrangements could be considered, it is necessary to ensure that two basic conditions will be satisfied; the first is that the two Boards or the Tax Departments should not act independent of each other; as we have stressed earlier, it is extremely important that the tax system is structured and managed as a harmonious whole and that other inputs besides knowledge of tax administration are brought into the formulation of tax policy.” (Para 9.28 of the Final Report Part – I)

Routine placement of officials in the two Boards (with little relation to length of tenure): Second, the selection of Chairs does not take into account the length of their remaining tenures prior to retirement. The selection is based almost entirely on seniority. As an indicator, in 2014 alone, there are likely to be four Chairs of CBDT and three Chairs of CBEC. For Members, there is a requirement of one year of residual service. Otherwise, the selection process is the same. With such rapid turnover and short tenures, there is little leadership in the Boards and, consequently, scant attention and time being devoted to directing national tax policies or providing administrative guidance – their quantity as well as quality have been reduced to random outcomes of ephemeral Chairs and Members.

Board assignment has little relation to experience or link to specialized areas: Third, the assignment of functions among Members does not necessarily reflect their work experience. Additionally, some areas that comprise crucial matters in modernizing tax administrations are given inadequate attention – for example, information and communication technology (ICT). Indeed, in such a specialized area, it is possible that people elevated to the post of Member ICT may have spent hardly any time during their earlier career on this matter. It, therefore, is unlikely that such a Member will be able to manage the area or take dynamic essential steps to keep the tax administration abreast of the latest developments in ICT applications that would be beneficial to the system.

Members making policy have little policy experience: Fourth, most Members emerge primarily or exclusively from field functions while, at the Boards, they are expected to design policy. Introduced policies, therefore, are often unrepresentative of the best available and experimented policy options from across tax administrations internationally. This happens even as top taxpayers express willingness to adhere to a rational tax administration framework while increasingly protesting against prevailing practices that do not compare with their experiences in dealing with tax administrations elsewhere.

Members’ risk aversion leads to low productivity or low motivation to provide guidance or clarity: Fifth, positioned beneath a Revenue Secretary picked from another Service, the Boards have tended not to assume a leadership posture, their views and decisions increasingly revealing extreme risk aversion. The outcome is that the Boards’ decisions or pronouncements in the form of legislative changes, binding circulars, clarificatory guidance notes or press releases are few and far between, and that too under external force, in contrast with other tax administrations elsewhere.

Risk aversion permeates down, and leads to, infructuous tax demands: The stance of inaction has permeated down to Chief Commissioners and even Commissioners who are averse to taking strong or even correct decisions that would counter infructuous demands made by lower level officers who have been given the role of a quasi-judicial authority. On the other hand, when an officer is convinced about a demand s/he has made but the Controller and Accountant General’s (CAG) auditor has disagreed with it, the Boards have issued standing instructions that a “protective demand” must be issued by the officer to the taxpayer. Thereafter, the departments persist in such futile litigation imposing completely avoidable costs on the taxpayer. The CAG has nowhere stated that such protective demands should be issued and it is entirely up to the Boards not to do so. Non-issuance could lead to their being called to explain by the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) of Parliament; this was not uncommon in earlier years. Where a considered view has been formed on CAG’s observations, the Boards ought to display the courage to defend their decisions before the PAC should such a need arise, instead of transferring the risk to the taxpayer. The Board’s standing instructions, therefore, reveals excessive risk aversion that could only have an adverse effect on the taxpayer who is left in a completely uncertain and trying position in terms of current cash flows and business decisions for the future. The deleterious ramifications for the economy can only be surmised but not exaggerated.

Taxpayers express helplessness against rude or arbitrary behaviour of officers with little assigned accountability in practice: The continuing impact on the taxpayer who has been relegated to a position of helplessness is unprecedented internationally. The confusing, if not arrogant, environment that they have to face on a daily basis was reported by high finance officials of major Indian corporations who are some of the largest Indian taxpayers. This occurred during the TARC’s stakeholder consultations at five Indian metros – Bengaluru, Chennai, Delhi, Kolkata and Mumbai. They did not complain about the disagreements of the quantum decisions as much as about the rudeness in communication, non-maintenance of appointment time, passing on accountability to another location, and going so far in some instances as informing the taxpayer that a demand is being made to obviate “vigilance” – internal audit against the officer – and the taxpayer should take recourse to the appeals process available to him. This matter is detailed further as it has cropped up time and again during consultations with taxpayers in different contexts.

Complete absence of economic, statistical, behavioural, or operations research-based analysis of policy or of taxpayers prior to making major or minor legislative or subordinate legislation-based (rule-based) decisions: Administrative decisions and tax policy making are both based on nil analysis by international standards. No “impact assessment” is carried out before introducing major legislative changes. Even changes in rules that Boards announce have no reference to what background analysis has preceded the decision. Pre-budget discussions are usually back-of-the-envelope calculations of revenue impact. The impact on a taxpayer is considered in a cursory manner, if at all. Retrospective amendments clustered during 2009-12 may reflect this lackadaisical approach. In turn, this reflects complete lack of accountability at any level except on grounds of lagging behind in revenue collection.

Lack of use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) based data by the Tax Policy and Legislation (TPL) Unit and the Tax Research Unit (TRU): The two departments on both direct and indirect tax sides have made impressive advances in the installation of ICT and its use in the process function. What has not occurred is data mining. The masses of data generated, for example through the expansion of electronic filing, remain essentially unutilized. In modernizing tax administrations, modelling of taxpayer behaviour to obtain nuanced taxpayer behaviour patterns prior to the formulation of tax administration policy has become common practice. India has not yet begun even rudimentary attempts in this direction. Given its current size and officer backgrounds, in fact, no essential tax policy or tax administration policy analysis is carried out at either TPL or TRU. They function essentially to interpret and draft the law. There is no officer who is, or could be, entrusted to carry out ex ante or ex post policy analysis. This points to the urgent need to overhaul these units on the basis of a total reformulation in their objectives and scope.

Adverse impact of revenue target on tax officer equilibrium: Revenue target is the sole criterion that is effectively used to assess performance. Targets are set in the Union Budget in a static context. No attempt has been made by the Boards to undertake any post mortem study that would analyse whether the projections were correct over a period of time when placed against the economic trajectory during the past year. Instead, the Boards pressure Chief Commissioners, who pressure Commissioners, who pressure lower level officers to meet fixed revenue targets, irrespective of the prevailing condition of the economy. Officers complained bitterly during the TARC’s consultations in the five metros about the anxiety that they go through on account of the revenue collection pressure and some even went to the extent of pointing to the need for mentoring, coaching and psychological support.

Blind revenue target causes unjust pressure on good taxpayers: Modern tax administrations do not use a fixed or static revenue target. A revenue projection is made at the time of the budget reflecting the condition of the economy at that point. The projection is changed during the year reflecting the changing economic outlook. This is compared against what revenue is actually being collected. The difference is called the “tax gap”. This is continually minimized through better collection efforts by reducing or eliminating tax evasion rather than by putting pressure from the top on officers below who, in turn, pressure even good taxpayers to contribute more revenue or postpone making due refunds in particular during the last quarter of the financial year. Such policies would be illegal in other law abiding societies. Consequently, instead of formulating policies with respect to tax administration and tax policy, several Board Members take on the role of tax collector.

The consequence, unsurprisingly, is twofold: first, a dearth of meaningful tax policy or tax administration policy and, second, an inequitable pressure on the good taxpayer. Indeed, the TARC observed, other than helplessness, deep and openly expressed anger amidst even top taxpayers in several metros.

Wrong use of tax avoidance instruments for revenue generation: In the direct tax area, ordinarily, transfer pricing examination between associated enterprises should be used as a tool to minimize tax avoidance. In India, transfer pricing measures are used for revenue generation, which comprises a completely wrong approach. This is revealed through the allocation of revenue targets to transfer pricing officers (TPOs) from transfer pricing adjustments. This is unheard of internationally. Accordingly, India has clocked by far the highest number of transfer pricing adjustments, demanding adjustments even for very small amounts. There is also a high incidence of variation among TPOs in their adjustments for similar transactions or deemed transactions. Taxpayers reported that they often succumb to such adjustments simply to carry on with business activity for, otherwise, they would have to allot or divert huge and unavailable financial and staff resources to such activities. Several other avoidance measures are also interpreted by the administration to be used for revenue generation, which comprises wrong policy.

Defective formulation and implementation of tax law and rules to generate revenue: On the indirect tax side, since the introduction of the “negative list” of services – only listed services are not taxed while all others are - has wreaked havoc among taxpayers due to poor management of change by the CBEC, reflecting lack of knowledge, preparedness or Board guidance to field officers leading to multiple interpretations combined with the usual lack of accountability for timeliness in clearing up confusion through circulars or guidance notes. The practice of delaying refunds by asking for irrelevant information reveals an undesirable and non-transparent practice to avoid refunding what is legitimately due to the taxpayer. Such artificial devices to garner revenue reflect an unethical approach to revenue collections.

Lack of quality in fiscal deficit reduction: Revenue target policy is usually set to achieve a better fiscal target figure. The TARC observes that the revenue target policy has been erroneous inasmuch as it is not just the numerical figure of fiscal deficit that counts but its quality. If a fiscal deficit is reduced through coercive government action in an era of global information, international rating agencies are going to take note of the overall business environment. Merely reducing the quantified fiscal deficit is not sufficient since the focus turns also to the quality of deficit reduction. Herein lies the fallacy of pursuing a blind deficit reduction policy. It has to be matched, instead, with appropriate approaches towards revenue collection both from tax administrator and taxpayer point of view. Indeed, some countries today are so concerned about the impact of tax policy and tax administration on the taxpayer that they have virtually removed the word “taxpayer” from the lexicon, replacing it with “stakeholder” and “customer”, recognizing them as partners with the administration in generating revenue. India remains a long distance from such an approach.

While revenue target is often achieved due to economic factors, identification of tax administration impact or tax-base impact is not separately attempted. Thus, the overall impct assessment is confined to a year, and no gainful change is made in the tax administration or conscious efforts made to widen the tax-base.

Escalation of disputes and poor recovery from demands: Lack of accountability in raising tax demands without accompanying responsibility for recovery has led to an unprecedented situation in India, which is experiencing by far the highest number of disputes between the tax administration and taxpayers with the lowest proportion of recovery of tax while arrears in dispute resolution are pending for the longest time periods. Thus, dispute management comprising dispute prevention and dispute resolution is at a nadir. It has also become a profession in its own right in a backdrop where, in modern tax administrations, disputes are entered into only as a last resort.

Virtual absence of customer focus: Much of the modernizing tax administrations across the world have changed their stance towards taxpayers in a visible change in the approach to dealing with them, which is to treat them as partners. Segmenting taxpayers according to their tax behaviour enables the tax administration to develop strategies appropriate for such behaviour and improve the collection mechanism. In India, no customer focus strategy has been developed based on segmentation analysis.

Examples of customer focus are few and there is no training for it, reducing taxpayers to a subservient status: It is true that numerous Aayakar Seva Kendras (ASK) are being set up at locations all over India so that a taxpayer can register a question and follow how the matter is progressing through the system. However, selected visits indicated a wide variation in implementation. Second, through installed ICT software, a taxpayer can log in to see whether and how much his tax deduction at source (TDS) has been credited. However, many lacunae remain in terms of non-matching and the system has been slow in correcting anomalies. Third, other than TDS, there are significant cases of mismatch between the ICT-based Centralized Processing Centre (CPC) and the information percolating from there to a taxpayer’s Assessing Officer (AO). Although the taxpayer suffers as a result of the mismatch, the lack of responsibility or accountability, leave alone timeliness in resolution, between the ICT and the AO for redressal of the mismatch is striking, despite ardent pleas from affected taxpayers, the latter sometimes even being subjected to scrutiny. Fourth, a common complaint made during the TARC consultations by high and low taxpayers alike was that the Indian tax administration was virtually the opposite of what is understood globally as customer focus orientation in terms of congenial attitude and polite approach to the taxpayer, or in terms of timeliness in decision making.

Instances of egregious tax officer behaviour: Taxpayers are subjected routinely to rude and arrogant behaviour, are made to wait hours – being called to appear in the morning though met many hours later, sometimes even in the afternoon – are asked to make photocopies of information already sent to the administration again during the visit without availability of copying machines, CEOs of companies being asked to appear when the CFO or an accounts official from the company would suffice. These characteristics signify practice that has descended to unprofessional levels, to put it mildly. There is no departmental training to behave differently; there are no guidelines or framework of rulesfor accountable behaviour. Yet the vision and mission statements of the departments pronounce their intention to care for the taxpayer by incorporating taxpayer perspectives to improve service delivery. The prevailing situation is so far from common global practice that, in the judgment of the TARC, there is likelihood of a tax revolt in the not so distant future unless emergency and compulsory training is conducted for officers, with strong cues from the leadership. Contextually, while Ethics, as a subject, forms a part of probationers’ training, Customer Focus is not addressed as a topic at any point in the officer’s career. This decidedly reveals how the tax administration has functioned, and continues to function, in isolation and in a feudal manner, protected by systemic job assurance and assessed highly as long as revenue targets are met. The distance of this framework and manner of functioning from authentic customer focus could not be greater. The need for remedy could not be more urgent.

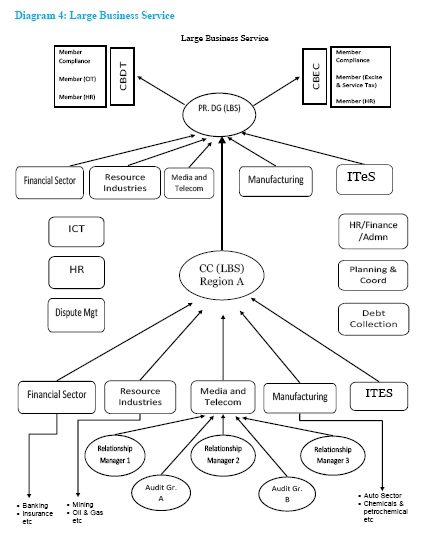

Large Taxpayer Units (LTUs): The concept of LTUs was introduced in 2006 following comparable practice in more than 50 countries. There should be a double dividend from the functioning of LTUs. On the one hand, large taxpayers defined according to their size of advance income tax or previous year’s excise tax or service tax payment, can pay all taxes –direct and indirect – at one window. On the other, the tax administration can be fully informed of all taxes filed by a single taxpayer – corporate or any other business – enhancing the sharpness of scrutiny and audit functions and their consistency across taxes. It is happenstance that in India, as explained above, direct and indirect taxes are divided into parallel departments with effectively little information passing from one to the other. The institution of LTUs was expected to bridge this gap at least for large taxpayers. This has simply not happened. While large taxpayers get the single window facility, the two tax departments have continued to operate as silos, desisting from sharing information even with respect to LTU participants. To protect their respective turfs, they have bypassed the advantages to be reaped from sharing information even when the revenue ramifications from such exchange could only be positive. Thus, so far, the advantage that should accrue to the tax administration by operating LTUs has not accrued at all. No viable explanation was received by the TARC as to why, despite the introduction of an institution at the highest policy making level, the administrative system could basically ignore the policy intention without the slightest retribution except, once again, to point to the complete absence of accountability in the system. The TARC has found that, were the functioning of LTUs to be revived to a pre-eminent status, they could form the fountainhead of tax administration reform in India. Chapter III of this report describes how the joint working between the two Boards in large taxpayer operations can transform the present working of the LTUs into a large business service. Diagram 4 below demonstrates that.

Irrational approach to vigilance over officers: Perhaps the most fundamentally diagnostic finding of the TARC is the almost absurd approach, by global standards, to vigilance over tax officers and the continuance of the system without the slightest revealed interest to change it from within i.e. by the Boards. A primary responsibility of the Boards is the welfare of and justice to their officers. Yet these officers are subjected to anonymous charges against them that could be ruinous to their careers. Vigilance action against them emanating from such anonymous complaints can drag on for years or be kept in abeyance only to be revived for unrelated future adverse steps that may be taken against them if the system so desires. It is not surprising that correct, fearless decisions cannot be expected from officers in an environment of such uncertainty. Instead, the safe course of action is to relentlessly follow the “revenue protection” goal that is inculcated in them as the primary motto of operation.

Fear of vigilance in management: The TARC found that a similar fear of vigilance lurks even in the higher echelons of management, rendering the administration devoid of bold or corrective action where needed or even where obvious. Unresponsive to taxpayers’ legitimate concerns, slow to undertake corrective action, on the contrary, instructing that protective demands be issued to taxpayers automatically on the basis of the CAG’s observations and ignoring its own officers’ assessment, the Boards – comprising top management of the tax departments – have succumbed to the fear of vigilance. The management is functioning to protect itself even while the taxpayer becomes its sacrificial lamb, revealing a lack of accountability towards the taxpayer. In this context, customer focus as enunciated in the vision and mission statements remains relegated to paper. Management becomes doubly irresponsible – towards both its officers as well as to taxpayers.

Fear of vigilance as a consequence of external pressure and external head: Possibly the subservient status of the two Boards reporting to an officer from a different service and, more so, without essential background or knowledge of tax matters, is leading to the Boards shirking from taking bold steps or corrective action, or being unwilling to face the legislative or judicial branches as needed, or being unwilling to take initiatives in the building of infrastructure or, last but not least, failing to empower the institution and, instead, remaining inert towards its own officers and taxpayers. All of this characterizes the Indian tax administration of the day. It is clear that unless it is given its own autonomy, the Indian tax administration can never rise to its full potential.

HRD – or People – function: First, while the need is to create a high-performing organisation, the HR policies of the two departments seem to work against the creation of a meritocracy. The promotion, transfer and placement policies do not adequately address the need for recognising merit, developing specialisation and creating a motivated and highly competent and professional work force, which is capable of effectively addressing the emerging challenges and also serving the taxpayers satisfactorily.

Second, several officers mentioned that there is a culture of supervisors doubting and questioning correct decisions merely because they are perceived as customer-friendly. This demotivates even diligent and honest officers and induces them towards risk-averse decisions, thereby passing on an unfair burden on the taxpayer as that would be an easy way out from being subjected to further questioning by management. In short, the common management stance being one of distrust of the junior officer, rather than his empowerment, sows the seed of a chasm between an officer and the management. The former eventually succumbs to the laid out approach expected of him by the system.

Third, the transfer policy of tax officers is routine if not archaic. The transfer policy needs to balance the needs of the organisation with the needs of an individual to maintain high morale. The argument that the Indian Revenue Service is an all-India service should not lead to the installation and functioning of a structure that ignores the need for specialisation. Transfers are given first priority over acquiring specialization in any subject that may be quintessential in carrying out acutely specialized tasks in a global context. An officer may be placed in TPL, TRU, systems, or international taxation, directly from the field without prior training merely to adhere to the transfer policy. Nevertheless, there are enough caveats in the policy to accommodate special ‘silver spoon’ cases. Indeed cases appeared to the TARC where circular transfer requests (pertaining to a group of officers) that are entirely connected ‘Pareto optimal’ – where there are gains without anyone being worse off – are ignored even where the transfer policy is apparently not compromised. Presumably this may reflect an underlying fear that such requests, if conceded to, may be repeated by others, not realizing that meeting such continuing requests would only enhance people welfare. The need for a transfer policy that is meaningful in its fairness and encouragement towards professional specialization cannot be over-emphasized.

Fourth, another oft ignored aspect of the people function is the implementation of leave policy. This appears to be randomly applied at least in selected observed cases. The policy has broad scope for leave accumulation, but granting of leave appears inexplicable and unrelated to the accumulation of leave. Rather, it appears to be linked to the professional relationship between an officer and his superior. The right of the officer to take accumulated leave has sometimes been ignored, revealing a lack of information or of training of managers in modern management principles in which rights such as the days of acquired leave, or stipulated number of days of training, comprise the right of a worker and has nothing to do with a work relationship. There is no redressal for the worker in such circumstances. What is worse, there is no accountability assigned to the errant superior. The TARC gathered the impression that the management tends to wield a tough stick on an officer who falls foul inter-personally of the system.

Fifth, an issue that cannot be ignored and appears to work in the reverse direction is that of moral hazard. Taxpayers openly complained during the TARC’s consultations about their helplessness against demands for bribes to make refunds, to hold back infructuous demands, or speed up processes from dormancy. While no officers’ names were mentioned for fear of retribution, the TARC views that the open claims made by stakeholders is a cause for deep concern. Even senior officers admitted their ineffectiveness in controlling this growing phenomenon. On the one hand, a toothless institution may suffer from various such maladies as almost a quid pro quo for the powerlessness that it endures. On the other hand, if the institution is responsible for delivering a public good and is intended to be the primary institution for generating funds for public expenditure, then bribery represents a leakage from public funds. Whatever tax is not paid and is shared instead between an errant taxpayer and a corrupt officer is an amount that does not enter the exchequer. This institutional disease, to the extent that it exists, cannot be ignored and a solution must be found.

Key internal processes: Glaring gaps prevail in internal processes. Some among those found by TARC are listed here: (1) a basic lack of harmony between direct and indirect tax departments; (2) relatedly, the issuance of PAN, its non-use thus far as a Common Business Identification Number (CBIN) and the lack of provision for de-registration, cancellation or surrender, and slowness in real time verification of PAN; (3) absence of possible consolidation of direct taxes on returns, for example, income tax and wealth tax; (4) continuation of jurisdiction specific returns for direct and indirect taxes; (5) lack of harmony even within indirect taxes, i.e., between customs, central excise and service tax, (for example, not combining audit of customs, excise and service tax paid by the same taxpayer, or not treating a business as a whole and instead treating it as individual audit units); (6) absence of e-invoicing and commensurate monitoring of CENVAT credit flow; (7) absence of audit protocols that separate different scrutiny procedures and protocols for different types of audits; and (8) the virtual absence of risk-based scrutiny selection for income tax despite the use of Computer Assisted Scrutiny Selection (CASS) due to lack of pre-selection data cleansing or systems-based checks and analysis.

A particular gap remains in an interface function with the taxpayer; this is in processing and making refunds.

(1) In the case of income tax, there is no time limit within which an AO needs to process the refund in case it could not be issued by the CPC. The insistence on manual filing of TDS certificates before the AO for verification of a refund claim stalls the process.

(2) Where eligible refunds emanate from Commissioner (Appeals), Income Tax Appeals Tribunal, a high court or the Supreme Court, again, the AO faces no prescribed time limit for issuing the refund.

(3) In the case of service tax, a consistent complaint was that of refusal to pay due interest to domestic suppliers and to service exporters under different pretexts – including repeated demands for additional documentation or the use of a provision entitled “unjust enrichment” – by the department. The latest available data reveal that, in 2010-11, interest on refunds was 0.01 per cent and 0.02 per cent of refunds for customs and excise respectively, which may serve as an indicator of the realism of the complaints.

(4) It was reported by officers to the TARC that it was routine to receive instructions from above to slow down or stop making legitimate tax refunds in the last quarter of the financial year.

Tax fraud, intelligence and criminal investigation comprise another deficient area.

The TARC found that:

(1) “Search and Seizure” and its legal backing need to be made clearer. Drafting of prosecutable issues and highlighting the offence and the evidence to be adduced either do not exist or are carried out not in a fully professional manner. A dedicated vertical assisted by lawyers is currently lacking and needs to be embedded in the administration.

(2) The directorate in charge of investigation of criminal activity on the direct tax side is inadequately linked to other agencies and, remarkably, not even to the indirect tax side. This once again reveals the deep and inexplicable chasm that continues to exist between the two tax departments and is simply tolerated despite obvious synergies that would ensue if common functions were jointly performed.

Role of ICT: ICT today is the most critical underpinning for tax administration reform. All modern tax administrations see it as a key component of their strategy to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of their operations, be it customer services, internal business processes or effective interventions in the area of audit and enforcement. They are also focusing on enhanced use of analytics to support their actions in diverse areas such policy making, customer segmentation and risk management.

While the two Boards’ achievements are creditworthy, and provide a robust basis for future progress, in the TARC’s opinion, there is a long road ahead of both the Boards before they could be said to have achieved comparable global benchmarks, of a modern 21st century tax administration, for full and effective utilization of the potential that ICT offers. And in order to reach that destination, they will have to chart a new path as TARC has outlined in Chapter 7 of this report.

ICT does not appear to be fully internalized in the thinking and working of the departments and there is not enough appreciation of its strategic importance as opposed to viewing it merely as a means of automation of transaction processing. The absence of integration of the ICT and business domains at the highest levels has led to sub-optimal realization of the benefits of ICT projects and systems. Greater attention is needed on the part of the senior leadership to the opportunities that ICT offers for re-engineering business processes to do things differently and more productively. Further, there is insufficient focus on the use of data analysis for developing policies and for making informed and evidence based decisions. It is true that the CBEC has already implemented, and CBDT is implementing, a data warehouse that will provide much better access to data as well as powerful analytical and reporting tools. However, in the absence of data sharing between the two Boards, the data warehouses will only provide data from their respective systems, and thus only a partial version of the truth, thereby limiting its utility. Further, merely providing technology is not sufficient. If the required human capacity to use the technology tools to perform advanced analyses is not developed, the potential of ICT will remain unrealized. There appear to be no efforts planned to create such capacity and develop an institutional framework for undertaking research and analysis in either of the Boards.

The implementation so far has been in the project mode, meaning that individual projects were conceived, designed and implemented at different points of time for meeting different needs. There has been no clearly articulated ICT strategy, derived from an overall organizational strategy and vision, forming the basis of the project development. This weakness has been compounded by the absence of a robust ICT governance framework that would have encompassed sound programme and project management, closely linking business goals with ICT implementation. It has also led to heterogeneous approaches to ICT implementation, with systems being developed along different implementation models and not adequately catering to the need of interoperability.

There are also gaps in the ICT implementation. These are either because some processes have not been covered in the scope of automation or because the sub-systems or modules that provide for digitization have are not been implemented. This is true of the core applications of both the direct and indirect tax administrations. The result is that data are incomplete and the Boards are still dependent on reports from the field, which, besides often being inconsistent and inaccurate, impacts on the efficiency of field operations.

Missing pieces in digitization of operations also means that the Boards are unable to make meaningful performance measurements at the organizational as well as at team or individual officers’ levels. Consequently, they are unable to effectively manage performance at all levels.

There also appears to be a communication gap between the DG (Systems) and the officers in the field, leading to difficulties in implementation as users do not seem to adequately perceive value in ICT implementation.

Many administrations adopt suitable ICT maturity frameworks, to assess their progress in ICT implementation, as also the comprehensiveness, depth and effectiveness of such implementation. No such use of framework has been adopted by the two Boards.

The most critical shortcoming of the current implementation arises from the two Boards operating in separate silos and a total absence of data sharing between the two. A big opportunity for radically improving both taxpayer services and enforcement actions is being missed on this account. An opportunity to reduce duplication of efforts and resources too is being missed.

The TARC also finds that a key risk to the ICT implementation lies in the HR policies of the two departments, which are overly oriented towards a generalist approach. Effective ICT implementation requires specialized skills and capacities and all modern tax administrations recognize this. In India, on the other hand, the transfer policy results in situations in which crucial resources get moved out the ICT function, at critical points of time simply because of the prescribed tenures, and new (and often unprepared and unwilling) persons get inducted. Combined with the absence of a reliable process of knowledge transfer, this continues to pose a serious risk to ICT implementation. Compared to the size of the projects, the two DG (Systems) are also understaffed.

Considering the complexity and scale of the tax administrations’ operations, and the challenges confronting them in a rapidly changing environment, the task of complete digitization of their operations is an onerous one. This, coupled with the need to take the implementation out of the silo-based approach that has constrained the realization of the full potential of ICT hitherto, would indicate that the DG (Systems) as they are currently configured and structured are ill-equipped to meet the future needs effectively. Only a purpose built organization that will take on the full responsibility for ICT implementation, with full operational freedom and flexibility to be run in an independent and professional manner, and yet be under the strategic control of and accountable to the two Boards, can successfully meet the challenge.

3. Conclusions

The critical findings delineated above, when combined, lead to the TARC’s overarching conclusion that, if an institution could have spirit, then the current Indian tax administration lacks that spirit. Functioning in a vacuum, it has lost its purpose as revealed in its behaviour, for its stated vision and mission are scarcely observed in its operational style. Its singular objective of protecting revenue without accountability for the quality of tax demands made is commonly believed to have severely affected the investment climate in India and in investment itself. This view reflects strongly the pleas, complaints and anger expressed by high and low taxpayers alike during the TARC’s stakeholder consultations. Thus, overall, the Indian tax administration is at its nadir. A fundamental and deep reform is urgently called for. There is no time to lose if investment is to be revived and its full potential reached, and an eventual tax revolt through capital flight or other direct protests is to be averted.

Deconstructing, the conclusions may be summarized as follows:

- A crucial deficiency is a fundamental lack of customer focus in the Indian tax administration, which is in stark contrast to modernizing and reforming tax administrations. The randomness and uncertainty in tax demands, the rudeness and abrasiveness in tax officer behaviour towards taxpayers, totally obviating the latter’s stakeholder role, the inconsistency in demands made on similar tax matters without accountability, and the often poor quality of show cause notices have combined to project the tax administration in its poorest light in the eyes not only of the taxpayer but of society at large. Yet there is no place for customer focus thus far in the training syllabi of either branch of the tax administration. Indeed, recently, the phrase “tax terrorism” has appeared in the gathering commentary on the Indian tax administration.

- The present structure of the tax administration – (i) headed by a non-tax official imported from another public service stream that has no link to taxation, (ii) artificially separating the tax administration into direct and indirect taxes headed by two parallel Boards for common functions, ignoring, for instance, even the functional commonalities in LTUs that were established for the very purpose of reaping benefits from exchange of information between the two tax areas, (iii) living with a selection system into the Boards that has no or little link to the length of tenure, work experience, or specialization, and (iv) risk aversion arising from an externally imposed vigilance over the entire officer structure – has led to a management functioning at a suboptimal quality and below its potential capacity.

- The risk averse behaviour of the tax administration has routinely led to infructuous tax demands on the taxpayer, often with the full knowledge that eventually such demands would not be able to withstand or pass the judicial process. In addition, a contrary view from the CAG on an AO’s assessment is directed by the Boards to be assimilated through a ‘protective demand’ on the taxpayer, despite knowing that it is likely to lead to a dispute. The resultant number of disputes and the time taken to resolve these have surpassed heights that are globally incomparable. The rules of appeal by the tax departments that elongate the process prior to final resolution and a high proportion of cases that end in eventual defeat have led to a miniscule proportion of recovery compared to demand. Yet there is no accountability regarding recovery for the concerned officer. While raising a demand is praised, there is no punishment for infructuous demands. The loser is the taxpayer in terms of time lost, advance payment required of the disputed amount resulting in deleterious effects on the cash flow of business, and the length of staff time and expenses associated with a long drawn-out dispute resolution process.

- The HRD or people function, or the approach to handling staff, is grossly inadequate. First, the pressure to meet exogenously imposed revenue targets, irrespective of the condition or prospects of the macro economy, has not only made it tough for taxpayers to make business decisions, it has also led to significant worsening in the officers’ work environment. Second, the tax administration subjects its staff to an irrational practice of vigilance in which anonymous complaints against them are given equal status to direct evidence. Vigilance emanates also from external agencies, which is not common practice in many other tax administrations. The outcome of the vigilance process can linger for years, truncating the possibilities of success in many careers. This fear starts from entry to termination of a career. The result is extreme risk aversion. Thus, an AO is likely to issue an order despite knowing that it would not withstand the judicial process, and higher tax authorities are unlikely to modify it for the same fear of vigilance. The loser is again the taxpayer. Third, the transfer policy and leave policy are irrational. They discriminate and tend to work against the good intentions of officers who have acquired rights to leave or have a genuine desire to specialize in a subject. Several officers expressed anguish over their dire need for counselling or psychological support. Such conditions are unheard of in modern tax administrations.

At the same time, accusations of moral hazard and demand for bribes cannot be ignored by the TARC. On the one hand, this could be partially explained through the administration operating as a subservient entity to another public service stream so that, despite an evidentiary slide in the morals of the institution, management does not feel directly responsible for it. On the other hand, given that the ultimate sufferer from corruption is the taxpayer – while recognizing that he has to necessarily be at least a passive participant – there is no gainsaying the fact that there is need for the tax administration’s management to take extraordinary steps to contain and obviate this institutional disease since it has a direct impact on society, its productivity and on the economy’s measured GDP.

The TARC, therefore, concluded that the people function of the Indian tax administration is in a very undesirable state. Even as the staff continue to exhibit competence, if not brilliance, at an individual level, the system tends to defeat them from performing at their full potential. Certainly, it tests them on erroneous premises and subjects them to archaic management practices. This situation demands immediate correction through compulsory training in modern management practices at the Commissioner and higher levels of seniority, who currently are subjected to little or no requirement for continuing management education. It also demands people policies that are designed to recognize and reward high performance, ethical conduct and identify leaders early and groom them for leadership positions so that they can lead the organisation to high performance. The TARC is, therefore, making recommendations in relation to this function which have transformative potential and which are radically different from the current processes.